The original Lancaster, of yesteryear, was designed for only one purpose, that of conducting the operations of mid-latitude heavy bombers; it was not really

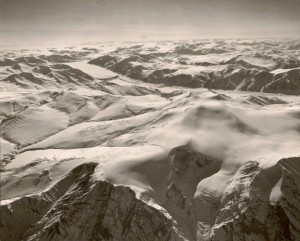

The original Lancaster, of yesteryear, was designed for only one purpose, that of conducting the operations of mid-latitude heavy bombers; it was not really  designed for activities in the high latitude winter arctic; but, it was all we had at the time. In these high technology days of satellite communications and precision navigation systems, it’s interesting to remember that earlier matters were not always so simple. In 408 Squadron’s Lancaster era the majority of Squadron operations were not in the mid-latitudes; but, rather in the low and high Arctic. Normal flight matters, such as communication; navigation; and routine maintenance, were rather more complicated and even potentially dangerous by comparison.

designed for activities in the high latitude winter arctic; but, it was all we had at the time. In these high technology days of satellite communications and precision navigation systems, it’s interesting to remember that earlier matters were not always so simple. In 408 Squadron’s Lancaster era the majority of Squadron operations were not in the mid-latitudes; but, rather in the low and high Arctic. Normal flight matters, such as communication; navigation; and routine maintenance, were rather more complicated and even potentially dangerous by comparison.

In the summer daylight months, most everything the Lancaster did and where it went was not so much different from that of any other aircraft of the time. However, in the winter nighttime arctic, aircrews had to be considerably more thoughtful in their decisions.

The Hercules and C17s of today have satellite communications and no doubt everyone has a personal small, somewhat thicker credit card-sized device that fits in a shirt pocket, to tell him where he is at any time, anywhere in the world (within a few feet).

However, unreliable communications and navigation were only the beginning of the potential problems. Lancasters do not like to be abandoned by their crews and left to cold-soak in extreme cold temperatures at any time ~ they seriously resist starting again next day, should that occur. Therefore, in preparation for the -45C (and many times colder) crew-rest timeframe in that 24 hours of darkness, it was necessary to first oil dilute the engines such that the diluted oil’s viscosity next day would ensure the engines could turn over and presumably start. Hopefully they would, in that engine covers and external heaters were not normally available. There was absolutely no hangar space in those days anywhere, save for Thule.

So … next morning, or whenever departure time required, after picking one’s way over the puddles of leaked red avgas; green coolant; and black oil, all that avgas previously added to the oil in the dilution process, had to be burned off and that meant the engines had to start. Then another complication arose; in that, with the cold soaking affects, the pneumatic air tank was unlikely to contain air ~ it never would pressurize well under those conditions ~ the seals would shrink in the cold and the air would more than likely all leak away. The result was no air for pneumatic braking (if we ever got started) and more immediately significant, normal engine starting required pneumatics. If there was no air, an emergency starting procedure could be used; however, that process involved a certain amount of risk, in that a fire could occur.

Okay then, let’s say the start was accomplished successfully (on all four individual engines). Before the burn-off could be timed, the engines had to all be up to normal operating temperatures and that took time ~ a lot of time. As a result, the aircraft also being at ambient temperature inside (that same outside -45C+/-), the crew took turns sitting in the pilot’s seat, to man the VHF while the engines got up to temperature; and that process could take 45 minutes to an hour. It wasn’t until the engines warmed up that any heat was noticeable inside and that was never enough. There was an internal heater located in the fuselage, left side, aft of the main spar (called a Janitrol) that supposedly could warm up the interior; but, it was difficult to start and potentially dangerous in doing so and over time the crews abandoned its use altogether. In fact it was useless; if it could be started it was necessary to almost sit on it to feel any warmth at all, and it never did have any chance of heating the aircraft interior.

At one point in the Squadron’s winter sovereignty era, an internal directive was issued stating that it was considered improper for Canadian Air Force aircraft, on a classified sovereignty mission, to operate from a USAF Base on Danish territory and therefore, ACs were directed to not use Thule, unless in an emergency. Well now, in those winter darkness significant minus temperatures, not many ACs had difficulty finding a need for hangar space in Thule; of that you can be sure! It is still a great comfort to remember the only reason those ops were safely executed was due to the superb servicing and maintenance standard the Squadron enjoyed, back at Rockcliffe, together with the professional competence of our crewmember Flight Engineers.

The Lancaster sovereignty operations on 408 Squadron of that time were a joy; it was surely the last place in our Air Force that an AC would be given a crew; and an aircraft; and a job to do; and a time to go; and whenever they returned was a matter left up to the crew themselves. Following that era I was personally in and out of the Arctic on a multitude of other all-season occasions and ‘things’ sure do change. A copy of the ‘Airforce Magazine’, a few issues back, showed a C17 at Alert ~ and I realised I was born 40 years too soon. Oh Well!

LCol (ret’d) Dave Ives

Allyson

Served as ground crew with 408 Squadron in the UK, late November 1941, early December 1944, Have updated the

408 Squadron Wartime Casualty List in the Squadron History Book, responded to Association postings and suggest the following sources for information on Douglas Harvey:

408 Squadron |History ISBN 0-920002-32-3, Copyright 1984, The Hangar Bookshelf. Believe the Aviation Museum, Winnipeg, sold copies of his book. Boys Bombs and Brussel Sprouts by J Douglas Harvey, Copyright1981 – All rights reserved, McClelland and Stewart Limited ISBN 0-7710-4048-2.

Undoubtedly a great pilot, a commendable war record, never in doubt but not always right. Numerous examples

of his lack of consideration for others and the impact of his hasty conclusions on their respective families.

Example:

Chapter, Press on Regardless

Page 159

“I lost two crew members who could not continue to fly Operations any longer. one was Ray our Radio

Operator, no last name, who bailed out on his sixth trip, preferring prisoner of war confinement to the

known horrors of flying ops.”. “Ray and Harry had worked hard and I considered them very capable airmen, but they simply couldn’t stand the strain of operational flying.”

No mention of a possible need to abandon aircraft or their subsequent bale out discussions. Moreover there was

is no guarantee of a successful parachute jump or the possibility he would not be killed by the Germans.

Regards

George R McKillop

New Westminster, BC.

I am looking for information about the WWII pilot Douglas Harvey who flew, among other sorties, in the bombing raid on Nuremburg. He was part of the Documentary “The Valour and the Horror’s” Death by Moonlight: Bomber Command.

This is a pretty old post but I can direct you to find out the information for Douglas Harvey as he was my fathers friend and my father is still friends with his son.