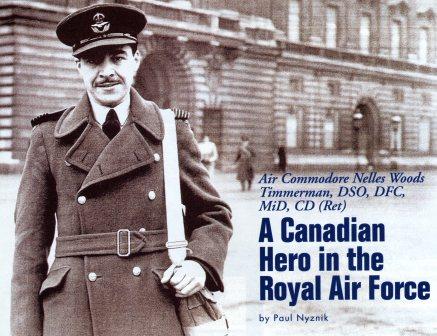

Attending to the needs of 600 longhorns on a cattle boat crossing the Atlantic may seem a strange way to launch a flying career. Yet, for Nelles Timmerman and a few other Canadians during the Great Depression of the 1930s, working his way to the U.K. and joining the Royal Air Force(RAF) appeared to be the only path toward realizing a boyhood dream.

From such modest beginnings it was impossible to imagine that by March 1942 Timmerman would have flown 50 operational sorties against Nazi Germany and would be summoned to stand before King George VI — first to receive the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) and again, to be presented with the Distinguished Service Order (DSO).

Timmerman was born in Kingston, Ont, on Feb12th 1913, the second of three boys. He received his early schooling there and planned for a career in engineering. However, financing a university education would prove difficult and, after completing two years toward an engineering degree at Queen’s University, the money ran out and Timmerman, now 21, was obliged to reconsider his future.

“I had always been keen on flying and decided that a private pilot’s licence might be an initial step to a career in the RCAF,” he recalled during a recent interview. But there was a matter of the $100, required for 10 hours of flying instruction.

To earn the money, Timmerman spent a summer working with a geological survey crew in Northern Ontario; then it was back to the Kingston Flying Club. He soloed in a Gypsy Moth after only six flying hours (there was no ground instruction), leaving a balance of four paid hours in which to hone his newly-acquired skills. Armed with his licence, he confidently presented himself to the RCAF. “Sorry,” he was told, “We are not recruiting. In any event, you would need a University degree in order to qualify.”

At the same time, word was about that the RAF was expanding and Timmerman, low on funds, explored the possibility of working his way to England.

The most promising offer was a job feeding and cleaning up after a load of cattle crossing the Atlantic aboard the Manchester Guardian. In return, while there was no pay, he would be assured of free return passage to Canada, should the need arise. The physically demanding trip took10 days, and on arrival in the U.K. in June :1936, Timmerman lost no time approaching the RAF.

He was accepted, subject to passing a short flying course at Scottish Aviation Ltd in Prestwick, Scotland, a civilian firm contracted by the RAF to weed out candidates deemed unsuitable for further training. He cleared that hurdle easily.

At RAF Uxbridge, near London, he was appointed to a short service commission, kitted, and spent some time “square bashing.” In Sept 1936, it was off to No. 10 Service Flying Training School (10SFTS) Ternhill, flying Hawker Hinds and Audaxes. In April 1937 he joined 49 Sqn RAF at Scampton, Lincs, resuming training in bombing and gunnery, photo recce and navigation.

Life in the early days of his career in the RAF was an easygoing, continuous adventure in many respects, with the prospect of another global war given little serious thought. As someone from the Dominions, his “proper” place within the British social structure was difficult to define. Nevertheless, he was accepted as a “classless colonial” and invited to spend weekends at stately homes and attend family gatherings on a fairly regular basis.

“When I received my commission in the RAF it seemed to legitimize my spot in the social order, which I’m sure was a relief to all concerned,” he said.

Timmerman flew his first wartime sortie on April 17th 1940 — a mine-laying (gardening) operation in the waters off northeast Denmark. By July of that year, after completing a tour on Hampdens, which included 20 trips over Germany, he was posted to a tour of instructional duty at No. 14Operational Training Unit (14 OTU), Cottesmore. When he returned to Scampton eight months later, it was not to 49 Sqn, but to its sister squadron on the station — 83 Sqn.

“I wanted to complete a second tour of ops in the hope that I could then go on to flying Beau-fighters. So I was racing like hell and went out on ops practically every other night,” he said.

Timmerman on the Hampden: “It was a great aircraft to fly, with excellent visibility from the cockpit, and responsive, superior handling characteristics, even at low speeds. I felt, however, that itwas poorly armed, with one fixed and one move-able .303 machine gun forward and twin .303 guns in the dorsal and ventral positions.”

Soon after the outbreak of WW II the Hampdens of 49 and 83 Sqns flew daylight sorties against bridges, railway yards, airfields and shipping, as well as gardening — the extremely hazardous task of laying mines in enemy harbors.

While he was reluctant to discuss details of individual sorties, a number of examples were found in military archives, two of which would prompt Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris to write: “This officer is up for a ‘cumulative’ award for a long series of resolutely and efficiently carried out special night operations, often under bad weather conditions, culminating in a successful attack on a flak ship. I now think he deserves an immediate award as the first Bomber Command pilot to bring down an enemy aircraft with his front gun, at night.”

The first of the sorties to which Harris was referring was that of April 23rd/24th 1940: On a security night patrol over Sylt, Timmerman located two flak ships. At 1,500 ft, in the face of intense anti-aircraft fire, two 250 lb bombs were dropped in each of three attacks. A near miss was scored on the first ship, which then disappeared from view. A direct hit on the second caused it to disintegrate.

The second concerned the trip of May lst/2nd 1940 when Timmerman, returning from an aborted mine-laying mission, spotted an Arado 196 seaplane flying in the opposite direction near Norderney in the Frisian Islands. He returned to give chase, and using his front gun, saw the Arado dive into the sea.

There was another. On June 17th /18th 1940, Timmerman had delivered his bomb load at Schipol airport, near Amsterdam, and was heading for home when he noticed that a returning enemy aircraft had turned on its landing lights. He quickly turned onto its tail, firing his front gun. As it was going down, he swept underneath, on the deck, as the rear gunner added another final burst.

A common thread runs through the citations which accompanied Timmerman’s DFC and DSO: a purposeful, single-minded determination to accomplish the mission. Excerpt: “So desirous was he of striking at the enemy that his squadron commander experienced the greatest difficulty in preventing F/L Timmerman from scheduling himself on every occasion the squadron was detailed for operations.

“He is the first pilot of a Hampden to destroy an enemy aircraft with his front gun. His enthusiasm, zeal, cool determination in the face of the heaviest opposition and the outstanding example he has set, are worthy of the highest award.”

Predictably, in Sept 1941, on the basis of his operational flying record with 49and 83 Sqns, he was awarded the DSO. At a chance meeting at 83 Sqn, early in 1941, Sir John Slessor chief of the air staff noted that Timmerman was wearing the recently-approved Canada badge and registered surprise to learn that he was a Canadian. About a month later he found himself posted to 408 Sqn RCAF as its first squadron commander.

“In June 1941, we had 16 Hampdens at 408 Sqn, operating from grass strips,” he recalled. “Bombing targets on the continent was largely ineffective because they were difficult to find and we had no radar aids to help us. That was why we went out, usually on an individual basis, looking for any enemy targets we could find. In 1940, when losses on daylight operations over the North Sea were unacceptably high, the RAF switched tonight ops. The RCAF followed suit some time later.”

Soon after Timmerman’s arrival at 408 Sqn, Handley-Page Ltd donated £50,COs were free to use the money as they saw fit. Timmerman decided to seek approval to create what would be the first badge for any RCAF squadron overseas. “My first choice for the centre of the badge was an autumn-colored, red maple leaf, but for reasons having to do with the rigid rules of heraldry, it was rejected. The Canada goose, which I thought was also native to our country, was quickly approved.

“As for the squadron motto – ForFreedom – it was an answer to a simple question, ‘why are we here?”

Timmerman left 408 in March 1942,ending his operational flying with a total of 50 sorties. He returned to Canada as chief flying instructor at 34 OUT Pennfield Ridge, NB, an RAF unit flying Venturas.

Returning to the U.K. in July 1943, he served in training and staff jobs until Nov 1944, when he transferred to the RCAF as chief staff officer for operations at RCAF Overseas Headquarters in London. In the immediate postwar period he went on to stints as station commander at Odiham, Topcliffe and Skipton-on-Swale.

In 1946, after completing more than 10 years of overseas service, he returned home to attend staff college in Toronto. A series of administrative positions followed, including CO of RCAF Stn Edmonton and senior air staff officer(SASO) at North West Air Command at Edmonton.

In June 1952, after graduating from National Defence College, he was promoted to group captain and moved on to become deputy director of air intelligence, then director of air operations at AFHQ Ottawa. A tour as chief operations officer (COpsO) with Allied Air Forces Central Europe in Fontainbleu, France, followed.

In 1957 he was appointed CO of Stn Chatham, NB, simultaneously serving as honorary aide to the Lieutenant-Governor of New Brunswick.

In 1961, by now an air commodore, he went to the 29th NORAD Region Missouri, as deputy commander. Four yearslater he left military service to become the director of Emergency Measures Ontario, a position he held until his retirement in 1978.

Today, A/C Timmerman leads a quiet life, and with Patricia, his wife of 58 years, maintains an active interest in current affairs. Last summer we met with A/C Timmerman in his Weston, Ont, home. In conversation, he preferred to downplay his wartime exploits, saying only that, “We were all given a job to do — and did it as best we could.”

Airforce: What was your reaction to the “Death by Moonlight” segment of the CBC documentary, “The Valour and the Horror”?

NWT: Not impressed — to put it mildly. In their criticism of Bomber Command operations the producers conveniently neglected to mention the desperate situation the Allies were in when A/C/M “Bomber” Harris assumed command in 1942.One must remember that we were fighting for survival. I’m not sure the British population would have stood up under the strain without hearing on the BBC every night that the RAF had been out, bombing German targets.

Airforce: Were there any casualties among your crew while on ops?

NWT: No. We were hit only once — over Berlin in 1941. There was a close call in 1940, when I was instructing Hampden pilots at No. 14 OTU Cottesmore. Our aircraft was totalled when we crashed into some trees due to fuel starvation. Fortunately, no one was seriously hurt and there were no disciplinary repercussions. One of our hairiest sorties was the mine laying trip to Brest Harbour when the German battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were there. We arrived over the target to find the Germans had laid down a thick layer of smoke, completely covering the harbour area, so that dropping our mine at the normal height of 1,000 ft was out of the question. We went down on the deck, barely skimming the water. The mine was released and we quickly turned for home. (Timmerman fails to mention the intense enemy fire they faced going in and coming away from the target.)

Airforce: Were there any episodes that you would describe as high or low points in your life?

NWT: There were a number of highs, including being able to contribute during my service with the RAF and RCAF; being hit by enemy fire only once during two years of ops and escaping unscathed; being presented with the DFC and DSO by King George VI (once in Buckingham Palace!). The low points: having to leave Queen’s University without a degree due to lack of funds; postwar, serving for two long months as a judge at the RCAF War Crimes Trials in Aurich, Germany. 0

(Ed note: Paul Nyznik of Nepean, in suburban Ottawa, is a former

navigator with 435 and 408 Sqns.)

Nelles Timmerman relaxes at his Weston, Ont, home with his ever-

present pipe.

Airforce Spring 2001 29